Record dry spell causing havoc for South East farmers

It may be green as far as the eye can see, but farmers in South Australia’s South-East are currently facing conditions they fear they may never recover from.

Bush Summit

Don't miss out on the headlines from Bush Summit. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Don’t be fooled by the lush green of the landscape as you drive through the flat, picturesque vistas on the traditionally rich and fruitful soils of South Australia’s South-East.

We’re here in the last week of winter, and it looks like we’re in a land of plenty – a region that Frodo Baggins could comfortably call home.

Sheep and cattle graze with seemingly careless abandon and it’s hard to fathom this is a district in the midst of record-breaking dry spell.

But it is. Welcome to the green drought.

Lifelong farmers say they have never experienced anything like it. Some say it will take five years to recover. Some say eight. Some wouldn’t be surprised if some of their neighbours don’t survive and are forced from the land.

Farmers’ bank managers and mental fortitude have been stretched to the limit as a severe lack of rain has forced them to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars and countless man hours handfeeding fodder to starving sheep and cattle.

Livestock numbers across the district have plummeted as farmers offloaded hungry mouths and made tough decisions about how to navigate an unprecedented dry spell.

Other sheep and cattle that couldn’t be offloaded have succumbed to their hunger, dying in the paddock.

Farmers supplementing their grazing with cropping were forced to dry sow – the practice of planting their grain before the traditional autumn break which provides the soil with the moisture a seed needs to germinate.

This is a measure becoming increasingly common in northern and western areas of the state, but one which those in the South-East, traditionally the wettest region of South Australia, have never had to worry about.

Until this year.

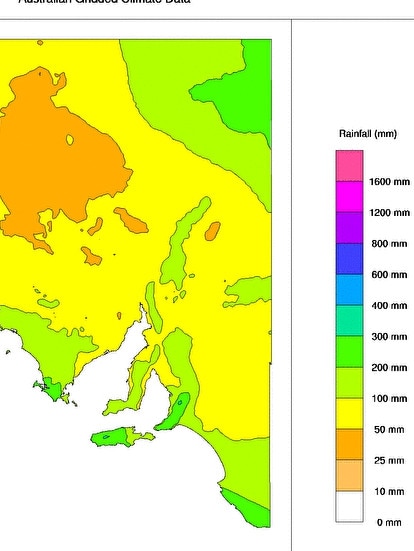

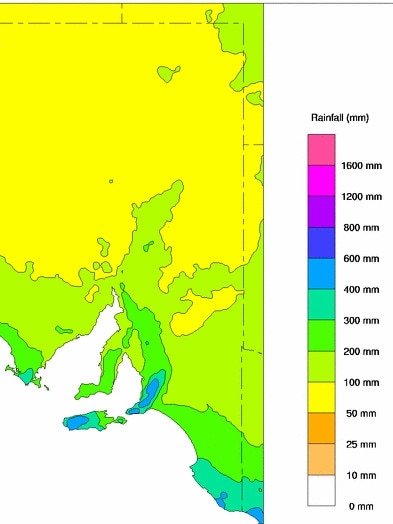

This year has been one out of the box. In the six months from February 1 to July 31, Mount Gambier received 246.8mm, compared to a mean of 373.3mm. Mount Schank received 199.4mm, compared to 391mm. Naracoorte has received 108mm, compared to a mean of 229.3mm. Millicent has received 230mm, compared to a mean of 414.9mm. Keith has received 106mm, compared to a mean of 233.2mm. And Lucindale has received 140.9mm, compared to a mean of 320.3mm.

Bureau of Meteorology senior climatologist Jonathan Pollock says the past six months have been the driest on record for the south of the state.

“From February until the end of July – that six months is the driest on record for a lot of the agricultural areas, including the South East, since 1900,” Mr Pollock says.

“Some parts in the south have a larger rainfall anomaly, but in terms of percentile ranking they’re all at the bottom of the data.”

For Peter Andre, this has meant he’s been manually supplementary feeding sheep and cattle on his 3200-hectare Kangaroo Inn property since November last year.

He reckons he’s spent upward of $700,000 on grain and hay, and perhaps another $100,000 on labour to distribute the food, a monotonous, daily task that comes with significant mental toll.

Mr Andre, 50, usually runs 1200 cattle and 7000 ewes on his land, about 30km north of Millicent.

He has managed to maintain his cattle numbers this year, but has downsized his sheep flock by about 1500 since the dry set in more than 12 months ago.

“At the start, there’d be a few sheep that you’d try and help save (from starvation), but then it got to the point you didn’t have time,” he says.

“Some were cast (stuck on their backs, unable to get upright) so you’d get them up. Half you’d get going. Others, you know, would be dead the next day. You just didn’t have time to drag all the dead ones away.

“There was no end to it. The mental side of it just hopping up and doing the same thing, the same thing every day …”

A dump of up to 50mm of rain over a couple of days in mid-August was the region’s best fall in more than 12 months and has provided hope at last that farmers might finally be able to stop the soul-sapping, money-draining exercise of handfeeding their livestock.

Some have been able to stop already.

Others, like Mr Andre, have wound right back, and expect to stop in the next few days. But they know they are by no means out of the woods.

Because if there is another dry spring and crops of hay and grain are down on average, the price of fodder next year could be even higher.

Anthony Hurst, 48, farms about 2000 hectares about 30 minutes north of Mr Andre at Avenue Range, west of Lucindale.

When The Advertiser visits him this week, he’s preparing to send about 180 cattle for agistment in NSW, to help take the pressure off his land as it attempts to recover from the record dry.

“We’re just getting stock out of here, pure and simple” Mr Hurst says.

“We’ve had no spring (rain) last year. We’re potentially not going to have a massive spring this year, and in our farm pasture systems, we need to have seed set.

“So we’ve got to have a natural seed laying in the ground ready for next winter. If we keep all our stock on, we’re not going to get that seed set to two seasons in a row, and that’s where we’re going to find next year will be in a world of pain again.”

Mr Hurst usually runs about 500 cows and about 6000 sheep.

Once these cows hit the road this week, he’ll be reduced to about 200 cows and 3000 sheep. Despite that stock reduction, he estimates he’s spent about $350,000 since he started feeding sheep and cattle in December.

He wants Adelaide-based politicians to come for a drive to regional SA and see the widespread effect of the dry throughout the state – not just in the South-East.

Because despite the rain of the past two weeks, farmers are still doing it tough.

“It’s been a bloody big challenge,” he says. “I know a lot of farmers, just after that rain event the other day, you could see a change in their mental personality. They were a bit more relieved and a bit of stress might have eased up a little bit.

“But that also creates more challenges with ongoing issues. We’re not out of the woods.”

Patrick Ross, 66, is the mayor of Naracoorte Lucindale council. He’s also been a farmer at Woolumbool, about 20km north of Lucindale, since the late 1970s.

As he shows us around his 1500-hectare property with dogs Doug and Stella in tow, he points out some paddocks which would normally be under water at this time of year.

Like others, he downsized his sheep and cattle numbers after predictions of the long dry but this didn’t prevent his fodder bill tripling in the past financial year, as he resorted to confinement feeding his livestock.

Like Mr Hurst, Mr Ross worries for the mental health of his fellow farmers.

“I know many of them were just distraught and had depression,” Mr Ross says.

“But farmers are very proud. They won’t own up to what’s really going on in their life. But everyone knows what’s going on, because we’re all living it every day.”

Mr Ross says he wouldn’t be surprised if the total fodder bill for all South Australian farmers south of the River Murray for the past nine months had topped a billion dollars – a figure that has had a massive flow-on effect to other regional businesses. And he says farmers are unlikely to start spending again for at least another 18 months.

“It’s a long, long grind,” he says. “It’s really hard every day. Another truckload of hay and grain comes in. So that’s another bill you scratch out the cheque for.

“You’re looking at your cash reserve just disintegrating. Yeah. It’s really, really tough. Really tough. There’s not a farmer in the landscape that hasn’t suffered.”

Read related topics:SA Bush Summit