Award-winning journalist Chris Masters’s interviews with veterans gives unique perspective to Anzac Day

AWARD-winning journalist Chris Masters gives a unique persepctive to Anzac Day through interviews with veterans from our oldest war and latest conflict.

ANZAC Centenary

Don't miss out on the headlines from ANZAC Centenary. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WHAT they so often remembered was the smell. Turkish rifleman Adil Sahan told me: “When the wind blew from the east, the smell went across to the enemy, but when the wind blew from the west it came over us.”

Victor Cromwell, an Australian 10th battalion soldier in the opposing trenches was another of many to recall the same.

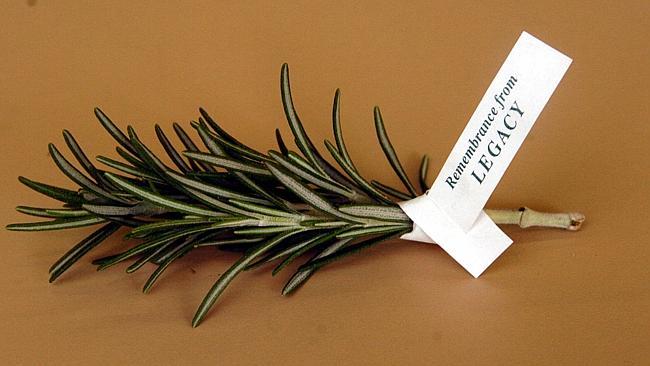

He said on later Anzac Days he would gag at the scent of rosemary, the herb growing wild on those perilous slopes, having intermingled with the smell of the dead.

I spoke to the men for a television documentary, Gallipoli, The Fatal Shore, made in the late 1980s when there was a last privileged roll call of veterans of that campaign.

In the decades following the Great War, the smell so often associated with memory was fresher. And the Anzac Days of those years were different for a nation afflicted with a grief that cannot now be imagined.

During that war on average 50 Australians were killed every day.

If you look into the eyes of the people of that time, observed on Anzac Days from our visual archive, you see the tears and pain.

But over time the smell of the dead passes and grief fades. And so 99 years on a mighty challenge presents itself to the organisers of the Anzac centenary. At the Australian War Memorial launch of the centenary program earlier this year director Dr Brendan Nelson spoke

of his frustration at having to constantly correct people who continued to refer to the approaching event as a celebration rather than a commemoration.

Lest we forget how badly we can get this wrong.

SPECIAL SECTION: 100 YEARS OF UNTOLD STORIES

Australia is rightly proud of its military history but Australians are no more warriors than war is sport. Claiming greater glory than is due is an offence to history as well as to former allies.

An outpouring of excessive sentiment is another poor look.

Young Australians are sometimes unconvincing in their rationale for undertaking the pilgrimage to Gallipoli; for the sake of closure with a great, great uncle they never knew. Or worse, wrapping themselves in the flag, loaded on booze, proclaiming with ignorance how their ancestors flogged the Turks.

Another danger of modern memory is the difficulty of recalling the smell, brutality, futility and heartache to a point where we might be left with a dry-cleaned account of action, heroism and adventure.

James Brown, a Lowy Institute Scholar and former soldier has written in a book, Anzac’s Long Shadow about the danger “of a culture in which looking back has become the major way in which Australians interact with the military”.

Standing at the intersection of two important national stories we might reasonably observe a keenness to insulate ourselves from the reality of old wars and new. As the centenary approaches we see the scaling down of the Australian role in what has become our longest war and, by my reckoning, our least understood war.

When reporting in Afghanistan I was sometimes surprised at the anger exhibited by Australian troops when discussing public engagement with the mission back at home. As the conflict bled on approval and support had dissipated.

Afghanistan was always a story to defy simple accounting, and the failure of our government to clearly define a convincing reason to stay on hardly improved its grip on Australian hearts and minds.

And Afghanistan was so different to the wars of old. No front line or trenches, nor even a clear metric for success. The objective was not to conquer but stabilise a broken nation.

A good day in Afghanistan was a day without violence. Soldiers who are trained to kill were constantly counselled to do the opposite. It can be hard to comprehend soldiers taking the lead in a humanitarian endeavour, but that largely was the task — of keeping the peace. The degree of difficulty is perhaps as hard to understand as the aforementioned depth of grief by our grandparents.

The Uruzgan province, where Australians were principally based, is like a landscape from another century. Literacy rates for males stood at around 5 per cent, and for females closer to zero. Tribal conflict is as intense as it is unfathomable. Government had little to no reach and when it began to push into the remote valleys, people of different tribal orientations as in past centuries, pushed back.

Trying to figure out how to help without making it worse was a daily dilemma. Corruption is so ingrained police and education budgets were routinely stolen.

Aid workers had to figure out ways of providing support without being ripped off by the governor or alienating a rival community.

Somehow young Australians had to mediate all this, setting out daily to protect communities, which all the while secreted bombs that might blow them to bits. It took some courage to continue to step out. There was another Afghanistan war too, which saw fighting and killing as up close and personal as at Gallipoli’s Lone Pine.

Conducted mainly by special forces personnel and therefore often in secret, the breadth of this other story remains untold.

If we could bring it all into better focus, Australians would observe a new generation rising, as at Gallipoli, to an impossible challenge. The contemporary Anzacs demonstrated time-honoured virtues of courage, persistence and responsibility to their mates as well as some mature restraint.

How ironic to think the modern military community, largely disconnected from mainstream Australia may be relegated to the status of a subculture at the very time the nation immerses itself in the culture of Anzac.

Come Anzac Day, let the columns form together joining veterans, young and old, Australians new and old, the civil, the military, mothers and wives, the protectors and the protected. Near one century on, we should be ready for a story of war that is honest and meaningful to all.

Chris Masters is the author of Uncommon Soldier